Almost, Later, Better, Already. We say these words all the time, but to a three-year-old they have complex meanings. As language forms in a child’s brain, how do these kinds of nuances develop?

In reference to a stoplight, my three-year-old granddaughter said, “Yellow means it’s almost time to stop.”

In her longing for warm weather she said, “We can run through the sprinkler later, when the snow is gone.”

After I suggested several ideas for lunch she said, “I have a better idea.” She wanted to have a tea party.

After I suggested several ideas for lunch she said, “I have a better idea.” She wanted to have a tea party.

When saying goodbye after a fun day of play she said, “I miss you already.”

The mystery of language has always fascinated me, particularly the progression from concrete thoughts to abstract ideas.

Linguists for many decades believed that our “mother tongues” held us captive. If you grew up in an equatorial climate, your language might not include a word for snow. Would that limit your belief that snow existed at all? Probably not. One can imagine the idea of snow by looking at photos in a National Geographic.

On the other hand, if you were an Eskimo you’d have over fifty words to describe snow. You’d understand the difference between wet snow, powdered snow, crystalline snow, falling snow, fallen snow, snow that’s been on the ground for a week, not to mention sea ice, which is altogether different. Snow would be your world, and so you’d know its many facets and forms.

On the other hand, if you were an Eskimo you’d have over fifty words to describe snow. You’d understand the difference between wet snow, powdered snow, crystalline snow, falling snow, fallen snow, snow that’s been on the ground for a week, not to mention sea ice, which is altogether different. Snow would be your world, and so you’d know its many facets and forms.

But what if there was no word for “grace” in your language. Would it be inconceivable? Would it affect how you dealt with offenses? Would there be alienation in relationships? Could you understand the centerpiece of Christianity?

In the late 1700s, Moravian missionaries arrived in northern Canada and discovered that the Inuit Eskimos had no word for “forgiveness” in their vocabulary. How could the Moravians explain such an profound idea to this people group?

The missionaries ended up creating a phrase for the concept of forgiveness—ISSU-MAGIJOU-JUNG-NAINER-MIK. This odd sequence of words meant: “Not being able to think about it any more.” They formed an association between “forgive” and “forget” using Jeremiah 31:34— “I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” Thus the Eskimos grasped the meaning of the Cross and reconciliation with God.

The missionaries ended up creating a phrase for the concept of forgiveness—ISSU-MAGIJOU-JUNG-NAINER-MIK. This odd sequence of words meant: “Not being able to think about it any more.” They formed an association between “forgive” and “forget” using Jeremiah 31:34— “I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” Thus the Eskimos grasped the meaning of the Cross and reconciliation with God.

Abstract meanings form because known words build upon other known words. And so people from different cultures can communicate.

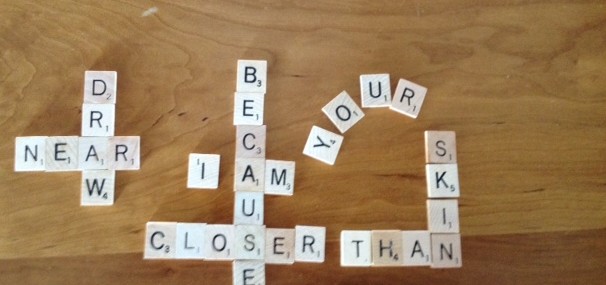

But language evolves, and maintaining connection with others requires constant learning. If you’ve ever felt left out in a conversation between teenagers, you know what I mean. Words like bromance, chillax, hashtag, and selfie are among 5,000 “millennial generation” words recently added to the fifth edition of the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary, published by Merriam-Webster.

But language evolves, and maintaining connection with others requires constant learning. If you’ve ever felt left out in a conversation between teenagers, you know what I mean. Words like bromance, chillax, hashtag, and selfie are among 5,000 “millennial generation” words recently added to the fifth edition of the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary, published by Merriam-Webster.

If we aren’t growing in language and communication, relationships suffer. And so it is with God.Continue reading